“When stock can be bought below a business’s value it is probably the best use of cash.” – Warren Buffett (at the 2004 Berkshire Hathaway AGM).

We covered this issue previously in June of last year, primarily from the economic angle, but recent events have appeared to politicise the issue. Several prominent Democratic Senators (Chuck Schumer and Bernie Sanders) want to prevent firms from buying back their shares unless they also increase worker pay and benefits, implying a link between low wage growth and high share buybacks. Marco Rubio, a Republican Senator has joined in. He wants to end the favourable tax treatment afforded to share buybacks (so that they are treated the same as Dividends for tax purposes). Thus, it is believed, firms may be more inclined to either pay out higher dividends or invest more in their businesses.

On top of the increasingly popular calls for a wealth tax on the “rich”, with some US politicians now set on introducing a financial transaction tax, there appears to be a sharp change in mood with regard to asset markets, particularly as last year share re-purchases surpassed the amount being spent on capital expenditures for the first time since 2008, partly as a result of the tax cuts implemented by Donald Trump last year.

The rise of “Democratic Socialism” in the US (and equivalent policy prescriptions elsewhere), has focussed attention on the dramatic rise in inequality (though some might argue that the Fed – and other Central Banks – are more responsible for this than are Companies, due to the former’s relentless pumping up of asset (i.e. equity) prices). The deliberate policy aim of generating a “wealth effect” [1], via higher asset prices has overwhelmingly benefitted the (already) wealthy as they own the bulk of the assets.

In theory, the way money is distributed to shareholders should make little difference to investors – the only practical impact lies in the tax treatment (dividends are taxable, re-purchases are not unless of course one sells the shares as a result of the price rise). This at least in part has been the main driver of the trend away from dividends and towards buybacks as a means of rewarding investors. In 1969, dividends represented 55% of all US earnings, (so the payout ratio was 55%); according to Goldman Sachs, the payout ratio for the S&P 500 is arond 88%, as of Q4 2018, only a little above the 140 year average. The recent rise may merely be a sign of the desire on the part of companies to increase their flexibility (as re-purchases can be amended as circumstances dictate, whereas the (negative) signaling effect of a dividend cut can be painful for shareholders, as share prices often fall sharply in that instance).

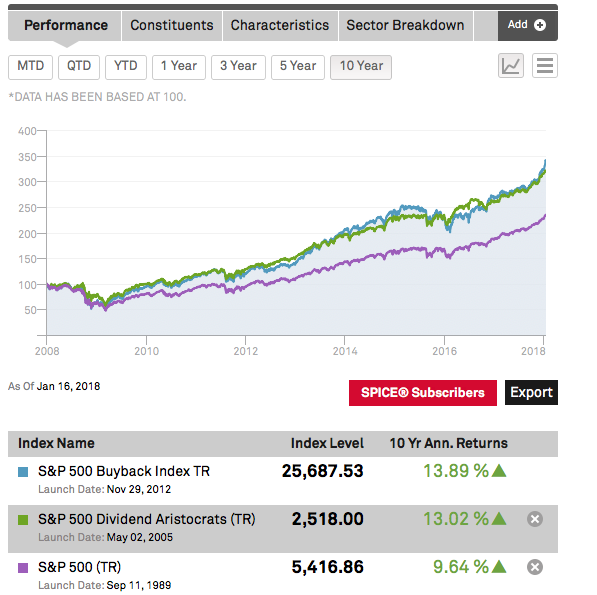

The political focus, however, has been on buybacks, but there is an irony here – over the last 14 years, the S&P 500 divisor (which measures the number of shares outstanding), has fallen by just 9.4% (which equates to a fall of just 0.64% per annum over that period). Even with all these buybacks, EPS has thus only been boosted by 0.7% per annum, whilst share prices have exploded, more than doubling over that time, which is a valuation issue NOT related to buybacks per se. The longest available chart (below), shows that companies that return money to investors via buy-backs have actually not done especially well relative to “Dividend Aristocrats” (those S&P 500 firms that have raised their dividends for 25 consecutive years or more), albeit better than the underlying Index. Although the oft-quoted numbers appear large ($2 billion announced here, $10 billion announced there), the market cap of the S&P 500 is currently more than $30 trillion dollars! Does this not signify much ado about nothing much?

At EBI, we have no political axe to grind either way. The overriding factor is one of capital efficiency; provided that there is no better use of capital (i.e. growth prospects are not superior intra-firm) or that the shares are trading sufficiently below the company’s cost of capital, there is no reason why executives should not buy back what would be “cheap” equities – as the reduced future dividend payment stream allows it to more easily fund future growth via increased free cash flow. It also has the benefit of reducing the scope for Corporate empire building (as the money for wasteful mergers etc. is no longer available).

The problem more recently appears to be that, incentivised by their own share option holdings, executives have used buybacks mainly to boost EPS and Return on Equity (by reducing the number of shares in circulation), pushing up the stock price and thus enriching themselves in the process. The buybacks seem to have soaked up the dilutive effects of their share options [2], with no corresponding benefit to shareholders – all these purchases have achieved is to remove the negative effect of effective share issuance, such that investors see no downside (but employees often do, either in the form of job losses or scant pay rises). Not that it has stopped share prices rising, which may be why shareholders have not really focussed on the issue.

But where shareholders fear to tread, politicians appear to have no such qualms, somehow believing that they have a better idea of how to allocate capital than do the management of firms. If adopted, it would create an extremely dangerous precedent, in that government officials (who in most cases have no business experience) imply that they know best how to run a company. There are countless examples of exactly the opposite (the UK Car Industry in the 1970’s springs immediately to mind) and it is but a short step from that to the chaos emerging currently in Venezuela when they have tried to run an entire country. Incentives matter and there are no such restraints on political ego in this situation, as solutions to perceived “problems” only tend to create new ones, (which of course justifies further intervention). Who knows where it ends?

[1] The theory runs that, if the value of their stock and bond portfolios rise, they will be more inclined to spend, pushing money out into the wider economy. It clearly has not happened, but Central Banks persist nonetheless.

[2] A grant of share options to an executive involves new shares being issued, which would, if left unchecked, would lower EPS, Return on Equity etc. because the same earnings would now be divided between more shares.